Steampunk Stahp! Or the Appropriation of Prada

Numi Prasarn is an artist, producer, and maker who has cut her teeth on a multitude of mediums and roles in the fashion and photography industries. Obsessed with fashion theory and with creating avenues for people to gain aesthetic control of their lives, Numi has turned to writing in places like Coilhouse and Pork Pie Hatters (and now Steampunk Workshop) to get her ideas on style and culture out.

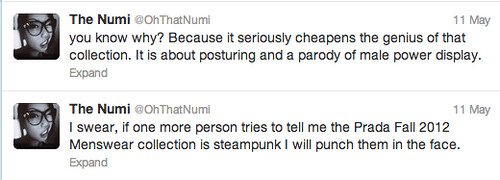

A couple of days ago I tweeted a mini rant about people tying Prada’s Fall 2012 Menswear collection to the Steampunk movement. It went a little something like this (Read bottom to top):

I figured it was time to stop just complaining and start some conversations.

My main complaint is that the collection’s initial message is being devalued and overlooked because of an easily thrown buzzword. My second complaint is that Steampunk doesn’t seem to be aware of where it stands in the grand scheme of things. First things first:

PRADA IS NOT STEAMPUNK (at least not in the way you say it is)

The collection in question is titled Il Palazzo. A Palace of Role Play. In a press conference following the show, Miuccia Prada lays it out flatly as a “parody of male power”; on programs and at the end of the show video it states, “…A cinematic character study, subverting male archetypes and formal codes of dress.” Pulling inspiration from the Victorian and Edwardian eras as well as 1960s Italian tailoring, the collection is a parade of formal wear bursting with signifiers of power and wealth that are then turned on their head. The high, layered collars and neckties point to the stiff styles of aristocracy of the late Regency/early Victorian era while also physically encouraging the wearer to keep their chin up (or at least give the illusion of a thick elongated neck and regal posture). But they are actually false collars attached to cotton tee-shirts/turtlenecks. The pinstripe “wool”, a pattern and fabric often associated as the armor of wealthy businessmen, is made of denim, a material historically associated with the working class (and now-a-days, casual wear). The “painted silk” of the bath/lounge-robe-as-outerwear-jackets is woven cotton. The prints that from afar seem like staid, baroque or paisley patterns are actually tiny american football helmets or guns. The vests and jackets all have front pockets from which boutonnieres, lapel pins, pocket squares, sunglasses and pens are crowded in – these are tools of business and politics, not craft. Actually, let’s focus on the lapel pins for a second. Historically used to denote achievement in an organization (military, fraternity, company, whatever), the pins in this collection at times refer to tools of violence and warfare (guns, arrows, shields, roman soldiers), and at other times sports references (football and football helmet, a skateboard that made me laugh). These lapel pins are ornamental and cartoonish displays of status and dominance and serve no utilitarian purpose. The double breasted buttons on the vests run into the pocket, making it known to those that notice that the button is nonfunctional. It doesn’t matter that everyone knows the second set of buttons is decorative, we still stick to the illusion. At every turn, there is a design element that shows the front of formality and status but upon closer inspection it is revealed to be phony and empty; a series of very well made skeuomorphs. This is Prada’s commentary on posturing and presentation: how much we rely on gesture and visual cues and how it is manipulation.

And throughout all of this meta-analysis, the clothes are beautiful and wearable. This is what pulls the collection from costume and performance and places it into fashion. Tim Blanks put it best when he wrote “An awful lot of ingenious thought had gone into making a statement about the emptiness of dressing to impress, while, at the same time, producing clothes that will entice men to do exactly that.“ It’s the ultimate middle finger! Prada manipulates you by using the historical language in dress, and even pulling them out of their original context it works. You look at the models and you say, “that is not a man. That is a gentleman. And I want to be him”, regardless of the fact that the trappings are fake. And because of all of this, because to me this is a powerful message done so precisely right, my eye twitches the moment I see someone superficially attribute this to the Steampunk movement.

Now, I must make this abundantly clear. I am not playing inspiration police. I am not saying no one is allowed to use Prada Fall 2012 and Steampunk in the same sentence or use these looks as a jumping off point to put together an original look. Please apply this however way you choose and do share. However, I think it is incorrect to say that this collection is inspired by or capitalizing on the Steampunk movement because it’s a weak link at best. It is unfair to suddenly say that anything that refers to Victorian clothing is clearly a sign of Steampunk’s influence because fashion has been pulling cues from Victoriana since… the Victorian era. You don’t get to say that Gunne Sax in the 70s was inspired by Steampunk to make Victorian/Edwardian style dresses. I mean you do, but you’d be incorrect. The connection also puts it in the terrible position that Steampunk commentary often finds itself, as being superficial and easily passed over. Every article I have seen that ties the two never goes deeper than the surface costume connection, when there is a wealth of commentary to be made. The reason I am so adamant about this is not to stop people from referencing the collection in the context of Steampunk entirely but to promote better awareness of why we are using it and how aesthetic movements actually evolve. As it stands, Steampunk wishes it was enlightened parody and commentary, but as a movement it is currently incapable of being so.

Steampunk is in this awkward position of being divided by intention and practice. The ideology of the culture has been fighting this uphill battle with its own popularity but instead of evaluating this it attempts to attach itself to other movements. Take for instance the Maker Movement, a tech-based culture that is based on DIY and empowerment. I often see people connecting Steampunk to Maker Culture and I have to argue that there is a distinct divide, and it is because of aesthetics. This is not a unique problem, I see this problem as part of a bigger story of globalization. The way we form identity today has been affected by the changing way we digest influence. We are inundated with information; we can’t keep up with viral imagery and meme culture. This places more importance on aesthetics for how cultures move because the signifiers are front and center. That is what we are moving and trading. Pinterest, tumblr, twitter, facebook – social media has allowed us to share at an unprecedented rate, but the cost of having everything in your face is it becomes harder to parse. We’re conditioned to remove content from context, visual cues are picked up and spread, taken out of its original hands with ease (case in point, Prada). We see only the silhouette of a culture and that is what sticks. Rarely is there dialogue that delves or shares the meat of a subculture. In fact, I think Steampunk is the perfect example of the effect of this phenomenon. It spread so quickly and so widely that it seemed instantaneous. From inception to explosion in just a few months, and yet the way it spread and the vocabulary that was shared and taught was largely through design and imagery, not the core of anti-mass production/DIY element, it was the aesthetics that differentiated it. A desirable trait, expression through a cultivated style, is turned into an easily simplified crutch that outlasts its purpose. Juxtapose this with the maker movement which has no particular design focus, it’s harder to appropriate the symbols and signifiers because they do not exist as a unified front. The silhouette of the culture is fluid. The emphasis is on the individual creators and projects not how they tie in to a subculture. The barrier to entry in the maker movement is making something, for Steampunk it is dressing. This is neither bad nor good, it just is what it is.

Bear in mind my interests lay very heavily in fashion theory, and I approach many movements from this angle because to me it offers a tangible narrative for how cultures evolve. It is trackable evidence of where ideology and practice lie and how we form identities whether through conscious efforts or not. I understand that Steampunk considers itself more than just a fashion movement and it is, however the predominant trait that binds it is not ideology but aesthetics. And this puts the movement at odds with itself if we consider the new mode of how we digest trends. It is completely fair to say that all of this is a reaction to modern times, a push for individuality in an increasingly impersonal and mass produced world, however it is not by any means alone in this and to have an effective conversation I think we need to look at Steampunk not as a savior or exception but where it fits in the bigger picture.

For decades cultural anthropologists have been wrestling with modernity. An ambiguous term, I’m going to define it for the sake of this article through cultural anthropologist Caroline Evans’ words in her book Fashion at the Edge:

The term ‘modernity’ is one of a triumvirate of terms: modernisation, modernity, and modernism. ‘Modernisation refers to the processes of scientific, technological, industrial, economic and political innovations that also become urban, social and artistic in their impact. ‘Modernity refers to the way that modernisation infiltrates everyday life and permeates sensibilities […] And ‘modernism’ refers to a wave of avant-garde artistic movements that, from early in the twentieth century, in some way responded to or represented these changes in sensibility and experience.

In her book, Evans uses this definition to contextualize the fashion industry’s obsession with death, decay, and spectacle during the 1990s. She even points out the use of historical clothing elements in 90s contemporary fashion (mostly in the luxury market), designers who pulled from the visual vocabulary of Elizabethan, Victorian, etc. costume as commentary. Her aim “…of juxtaposing… manifestations of the consumer explosion of the nineteenth century against those of the late twentieth… to illuminate the way that the past can resonate in the present [and] articulate modern anxieties and experiences” resonates soundly with Steampunk, but is neither unique to it nor is it effectively explored. This is exactly what rubs me the wrong way about the Prada issue. It is taking credit for something it has yet to do.

I love aesthetics, I love design and how we use it to form and signal identities, but if we want to be able to move freely, remain informed, and use it effectively we have to call a spade a spade and realize how this works. Because what we really need to have is a conversation on modernity, a conversation that is being had in other movements including the luxury fashion industry but not here. And that is important. So let’s use the full extent of our resources to pick at that.

Runway images courtesy style.com