The Nine Novels That Defined Steampunk

By Johnathan Greyshade

The Nine Novels That Defined Steampunk

I’m a librarian by profession, and a scholar by inclination, so when I got involved with the amazing confluence of ideas that was steampunk in mid naughts I naturally wanted to know where this idea of steampunk came from. Most steampunks know little about steampunk’s origins. We are part of a strange phenomenon in which loads of elaborately costumed people call themselves “fans” of books they can’t even name. This is not too surprising since steampunk didn’t become popular as a genre until after it inspired an art and lifestyle movement. The few histories of the genre are too lengthy for most people to digest, but not knowing the basics about where steampunk came from leaves its enthusiasts wallowing in a shallow puddle of clichés when they could be swimming in an ocean of imagination. As a cure I suggest the reading nine of the most creative works of late twentieth century speculative fiction, the novels that defined steampunk.

The Original Steampunk Novels

A popular idea is that H. G. Wells and Jules Verne were the originators of steampunk. This is not really true. Despite its anachronistic veneer, steampunk is a very contemporary genre expressing contemporary interests and concerns. Wells, Verne, Shelly and others are important sources of inspiration for steampunk but they are not steampunk authors themselves. They wrote in a nineteenth century or nineteen century inspired setting because that’s when they lived. For a modern writer full of current ideas to choose such a setting is a totally different thing. There are isolated examples of writers revisiting Victorian settings throughout sci-fi’s history but steampunk as a word and concept has a clear origin in a letter to the science fiction trade journal Locus published in April 1987.

Dear Locus,

Enclosed is a copy of my 1979 novel Morlock Night; I’d appreciate your being so good as to route it Faren Miller, as it’s a prime piece of evidence in the great debate as to who in “the Powers/Blaylock/Jeter fantasy triumvirate” was writing in the “gonzo-historical manner” first. Though of course, I did find her review in the March Locus to be quite flattering.

Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term for Powers, Blaylock and myself. Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like ‘steam-punks’, perhaps.

—K.W. Jeter

Jeter’s letter tells us three important things.

1. K. W. Jeter invented the word “steam-punks” to describe authors of “gonzo-historical” “Victorian fantasies”

2. The other two steam-punks were Tim Powers, and James Blaylock.

3. Morlock Night was the earliest of the novels in the newly named genre.

Powers, Blaylock, and Jeter wrote a lot books between them, but of all the novels they wrote by 1987 only four of them were “gonzo-historical” “Victorian fantasies” so the original steampunk genre consisted of only four novels.

Morlock Night by K. W. Jeter, originally published in 1979

There is no clearer illustration of the distinction between steampunk and original Victorian adventure stories than comparing H. G. Wells The Time Machine to Morlock Night. Wells’ novel is a straightforward story about a device that allows one to travel in strictly linear time. It expresses the common modernist idea that technology can do anything but may destroy humanity in the process. In Jeter’s book the Morlocks seize the time machine and invade 19th century London with it. It takes a Victorian premise and mashes it with Arthurian legend and lost technology from Atlantis. More than thirty years after it was written it is still too “experimental,” for many people’s tastes. If read with an open mind you will find an adventure story with some highly imaginative twists. It shows the roots of steampunk as literature that took genre assumptions, smashed them, and made mosaics out of the most interesting bits.

The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers, originally published in 1983

This novel won the Philip K Dick award. It is stunningly well written. The central character is an English professor who travels back to 1810 to attend a lecture given by English poet. When he misses his return trip he must survive in City plagued by a mass murdering Egyptian god and an evil sorcerer clown. The plot snakes around like a serpent in the dark London sewers where so much of the action takes place. What is most surprising is how Powers combines a very hard science fiction approach to time travel with some of the creepiest portrayals of black magic you will find in late twentieth century writing. It’s worth noting that while Jeter grouped this book with his “Victorian fantasies” it is actually set in the last year of the reign George III.

Homunculus by James Blaylock, originally published in 1986

Homunculus by James Blaylock, originally published in 1986This is the first book about Professor Langdon St Ives and his archenemy the wicked Dr Narbondo. It involves a ghostly dirigible, undead slaves resurrected with fish guts, a stranded space alien and lots ofLaphroaig whiskey. Blaylock writes with a dry absurdity that seems very English especially when coupled with his Victorian wording. One of my favorite scenes is when the Trismegistus Club debates what to do while smoking and drinking to the point of incompetence. Not exactly the behavior of heroes but a brilliant satire of the chattering classes.

Infernal Devices: A Mad Victorian Fantasy by K. W. Jeter, originally published in 1987

Infernal Devices: A Mad Victorian Fantasy by K. W. Jeter, originally published in 1987Not to be confused with Philip Reeve’s or Cassandra Clare’s later works by the same name. Jeter’s Infernal Devices is one of the funniest steampunk books ever written. The central character, George Dower is a hapless English “every man” character comparable to Arthur Dent in Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. All sorts of absurd things happen to Mr. Dower until the madcap plot is tied together with an elaborate dig about Victorian sexual repression. This was the first novel in the genre to heavily feature clockwork technology but there are elements of pure fantasy as well.

Two Important Steampunk Novels from the Nineties

It took twenty years for “Victorian fantasies” to become “the next big thing,” but once the genre had a name it did become a small thing. Several books were published during the early nineties. I think of this as the second, or post definition, wave of steampunk. There was third wave around the year 2000. For the sake to brevity I will present only two particularly important second wave books.

The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, originally published in 1990

The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, originally published in 1990In 1990 William Gibson was one of the hottest names in sci-fi. When he and Sterling published this Victorian cyberpunk alternate history many people, including myself, were introduced to the word “steampunk” for the first time and assumed that the two of them had invented it to describe this one novel. It’s a serious, hard science fiction story set in a parallel universe where Charles Babbage’s calculating machine was actually mass produced and used to create an information age one hundred years earlier than in our time line. The exceptional world building for this book completely overshadows its mystery plot, but one has a fine time sightseeing in a version of Victorian London even more foul and industrially polluted than the original.

Lord Kelvin’s Machine by James Blaylock, originally published 1992

Lord Kelvin’s Machine by James Blaylock, originally published 1992This novel continues the adventures of Langdon St Ives. The book is really three sequential novellas. The first one begins with murder of Langdon’s fiancé at the hands of the Narbondo. This cruel act sets the tone for a less humorous but more ambitious work than Homunculus. A grim Professor St Ives must save the world not only from Narbondo, but from the misguided Lord Kelvin’s whose machine could destroy the world. The second part continues the struggle to keep Lord Kelvin and his machine separate. In the third part our hero extends the technology of his rival and uses it to set everything right. This exceptionally well-crafted novel comes to very satisfactory conclusion when the Professor decides that he loves eggplant.

The Proto-Steampunk of Michael Moorcock

While the word “steampunk” wasn’t coined until 1987 there were other intersections of quasi-history and science fiction in comics, television, film and occasionally books. In literature, Michael Moorcock’sOswald Bastable novels were the most influential by far. It was Moorcock who enshrined the airship. Homunculus and Infernal Devices each featured a small dirigible, but in the Bastable novels thousand foot long queens of the sky are a central theme.

Warlord of the Air, originally published in 1971

Warlord of the Air, originally published in 1971Bastable, a soldier of the British Raj becomes lost in a sinister Himalayan temple and immerges in the year 1973. This is not the 1973 we know but world where the British and other European empires are thriving and great airships fill the skies of seemingly utopian cities filled with steam-powered cars. All is not well however and Oswald is eventually captured by a “warlord,” who shows him the hideous oppression that underlies the world’s empires. Ultimately our hero joins the Communards in their resistance. Bastable is thrown back in time to 1906 but sadly it is a subtly different timeline were his own family thinks him an imposter.

The Land Leviathan, originally published in 1974

The Land Leviathan, originally published in 1974Desperate to find his true home he returns to the temple and immerges in another version of 1906. In this world the (very steampunk) inventions of the brilliant Manuel O’Bean powered a hideous war that devastated Europe, the Americas, and much of the world. Bastable eventually becomes the envoy of South African President Mahatma Gandhi to the New Ashanti Empire of Cicero Hood. A former American slave, Hood invades what remains of the United States and liberates its dark-skinned people. After discovering that most of the whites in America are just as wicked as Hood claims, Bastable joins his cause even though, as a white man, he will never be accepted in Ashanti society. In one novel, Moorcock invented both post apocalyptic, and multicultural steampunk.

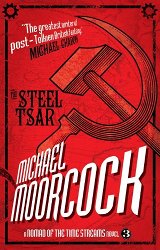

The Steel Tsar, originally published in 1982

The Steel Tsar, originally published in 1982Moorcock originally wrote this novel during a painful divorce. The version he rewrote for inclusion in the Nomad of Time Streams omnibus in 1995 is much stronger. Set in a 1941 enveloped in a global war very different from our WWII. Bastable survives a harrowing airship crash and goes on to fight “the Steel Tsar” who is none other than Joseph Stalin. Stalin is revealed as a petty egomaniac and dictator in any universe. At the end of the novel Oswald learns from Moorcock’s recurring character Una Persson that he is doomed to wander through alternate universes forever but is not alone in this fate. He finds solace in the Guild of Temporal Adventurers and Una’s embrace.

Clichés Broken

The steampunk written today is part of a fourth wave. While some of it is quite good there are a great many writers that go steampunk gatherings, take notes, and sell the fantasies of their target audience back to them. Not only does this produce terrible books, it leads to creative stagnation on both sides. A review of classic steampunk smashes many current tropes.

Steampunk isn’t just Victorian. By including The Anubis Gates in the works Jeter dubbed steampunk he made it clear that he meant Victorian as a stylistic generality not a set of dates. Moorcock further disproves the idea that steampunk is strictly Victorian. In Morlock Night, Jeter flits through time beyond the Victorian era. Steampunk is generally Victorian in flavor but it has no fixed period.

Steampunk is not about the aristocracy. Politically conservative steampunks often try to exclude Michael Moorcock from the genre because of his explicitly anarchist/left political messages. Even if we humor them, Jeter, Blaylock and Powers used Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor as their major reference and their work portrayed poverty frequently and unflinchingly. There are only two prominent aristocrats in their collected work, Lord Bendray in Infernal Devices, and Lord Kelvin in Lord Kelvin’s Machine. Both characters nearly destroy the world through their arrogance and foolish abuse of technology. In The Difference Engine the aristocracy is made up the merit lords of the Industrial Radical Party. The London they govern turns into a hell on Earth. Classic steampunk has nothing nice to say about the power elite. Those who pontificate about Victorian manners or style themselves unsatirically as lords and ladies need come to terms this fact.

Steampunk isn’t always about gadgets either. Steampunk technology is not featured in Anubis Gates at all. In Homunculus it takes a backseat to supernatural elements. Goggles are only mentioned once in theIndifference Engine and not at all in the other novels. Certainly no one in these stories walks around with gizmos hanging off them like Christmas tree decorations, nor do they seem to have any particular fondness for the color brown. If you’re tired of the many barriers that seem to box steampunk in you have only to look at its roots. The barriers were never really there.

About the Author:

Johnathan Sebastian Greyshade has been involved with steampunk since the early days of the brass goggles forum. He and his wife kick started the steampunk community in San Diego California with a series of gatherings under the name Machina Fatalis. They went on to run Chrononaut, a steampunk club night that ran for two years. These days he DJs the occasional steampunk gig but his primary focus the Greyshade Estate where he applies steampunk philosophy to building a sustainable urban homestead.

Comments

I completely disagree that Jules Verne was the father of science fiction. What about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein 1818? Or frankly, The Brothers Grimm? Jules Verne was a very important writer, but to assert that he originated science fiction is ludicrous.

Allyson, O Thee Fount of All Knowledge….

Well, s$@*. I only wanted to thank Johnathan Greyshade, especially for the list of books, but now I am just ticked and sad & being sarcastic. If you disagree with this whole article, that is 100% fine. Find a way to share your opinion without missing the point or using your superior brain to make this Blogger feel something clearly intended to be negative. The IRONY is that your whole comment is about a line I cannot find, and a subject – science fiction – that is not the genre or sub-genre (I love libraries but sadly am not conversant in that aspect, I apologize and hope I got close enough to be understood) that is written about above. I came to find out more about how Wells’ writings influenced Steampunk. Let’s type about that, sound good to anyone?? You missed an entire forest for the sake of one your bratty tree. How sad for you! And I mean that sincerely.

I thought comment sections existed so we could talk about what was written, not skewer the writer. Silly, stupid me. :/ Why do people who talk about Steampunk in comment sections get so mean? If this had been the first post I had seen all night, I would not have felt the need to write this response. But it is everywhere! I left the clothing Blogs to look at the Lit ones, and still, this same crap. Is this what you would say if you found yourself a guest in the home of a stranger? If we would all realize that commenting on a Blog or a FaceBook post is the “virtual” version of that, maybe the Internet would not have so many bullies. But it seems to just be getting worse.

Thank you for the Blog, and I am really sorry I was unable to just ignore the non-constructive critique. Maybe my skin will toughen up, or people will learn to be decent.

Agreeable… Much less exhausting than confrontation… However, I cannot allow this item to pass without, at the very least, pointing out the huge flaw in the diamond that no one wishes to see…

It is painfully obvious that the “Steampunk” interest, or fad if you wish, is an idea that jumped out of the head of Jules Verne… research the dates… H.G. Wells came onto the idea very shortly thereafter… A cursory look at the dates confirm that Jules Verne is the originator of science fiction… that is, fantasy and adventure-travel stories steeped in science…

When one speaks of “Steampunk”, they are defining it in terms of a certain set of Jules Verne’s novels…

1851 A Voyage in a Balloon

1863 Paris in the 20th Century

1863 5 Weeks in a Balloon

1864 Journey to the Center of the Earth

1865 From the Earth to the Moon

1866 The Adventures of Captain Hatteras

1869 20,000 Leagues under the Sea

1870 Around The Moon

1871 A Floating City

1873 Around the World in 80 Days

1874 The Mysterious Island

1877 Off on a Comet

1881 800 Leagues on the Amazon

1886 Robur the Conqueror

1894 Captain Antifer

1904 Master of the World

The H. G. Wells novels that influenced “Steampunk” are as follows:

1895 The Time Machine

1895 The Wonderful Visit

1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau

1933 The Shape of Things to Come

1896 The Wheels of Chance

1897 The Invisible Man

1898 The War of the Worlds

1899 When the Sleeper Wakes

1901 The First Men in the Moon

1904 The Food of the Gods

1905 A Modern Utopia

1906 In the Days of the Comet

1908 The War in the Air

1923 Men Like Gods

1924 The Dream

When I see fiction novels that are adventure stories of travel around the globe and into space, filled with science for the layman… good guys and bad guys… moralistic endings… wooden structures with iron, brass and copper… steam engines and pneumatic control systems… analog gauges and meters… rotors, propellers and dirigibles… divers in deep sea diving suits… coal fed steam boilers… para-military types in goggles and leather gear… defying survival under the sea… in the air… high in the mountaintops… on the moon… under the earth… I can only think of Jules Verne… then I think of H.G. Wells…

Even the term “Steampunk” is a poor descriptor… “punk” has no bearing on the matter… perhaps there is too much acceptance and following along… crowd shadowing… too many entrepreneurs and novelists controlling the flock to their own advantage… a better title could be “Vernean Sci-fi”… or even “Victorian Sci-fi”… however, the damage is done…

“BUT… I do not think of the nine authors and books listed by this blog… they may be fine books of today… but they do not define “Steampunk” by the very fact that Jules Verne predated them by 150 years… and H.G. Wells by 120 years… no…

people immersed in “Steampunk” are immersing themselves in the novels of Jules Verne, who juxtapositioned the steam power of his age with futuristic ideas and fantastic plots… the father of Sci-fi… all who came after are his heirs…

I agree with a lot of your points, but all those ellipses make you sound like an arrogant, self-important twat, which I’m sure you are.

this academic investigation into the origins of ‘steampunk” or what constitutes ” steampunk” is fun but totally limiting in scope. books by Scholes, Clockwork Vampires by Remic and Lawence’s great The Liar’s Key are steampunk but don’t take place in Victorian times – not the intrinsic for me a reason for a book to be labeled steampunk. these imaginative writers have moved gears low-tech and even magic into post-apocalyptic realms. leave the Victorian era behind it’s more fun and enlightening

While I understand that the term steam punk is of nineteen 80s , its important in my opinion not to

overlook or underestimate HG Wells and Jules Vern . Their was no term, when they wrote for what we would now accept as science fiction ,as Clark and Asimov evolved computer technology up to and including AI . So Vern and Wells did no less with Victorian technology , Verns use of an engine to drive the Nautilus was a giant step, as in fact was his establishment of underwater breathing apparatus . Wells Time Machine ,and his short stories, including drugs to speed up the Human metabolism, so as to make someone invisibly fast are still themes very much in use. So it is not so much a basis on Victorian London , but very much the imaginative use of technologies , which were only held back by the absence of modern material’s . We call it steam punk ,but we are brothers in a sense to Verne and Wells and many other Victorian writers in that we get our inspiration from ,not what is now, but what might be from what was

“While I understand that the term steam punk is of nineteen 80s , its important in my opinion not to

overlook or underestimate HG Wells and Jules Vern .”

The author of this article begins the second paragraph with discussion of Mr Verne and Mr Wells, that he feels they were not the first writers of this genre… well, probably better that you read for yourself rather than I sum up and mess up. 🙂 From my little bit of knowledge, and this seems to still be up for debate, Steampunk IS set in the “Victorian Era”, so not the 1980s when the Blogger posits Steampunk became a genre or sub-genre. Some people have said that it lasted “until 1940”, but I disagree. The Victorian Era very specifically was when Queen Victoria ruled England (20 June 1837 until her death, on 22 January 1901) but for Steampunk, the ideas of extreme modesty in outward appearance mixed with the discoveries of the time sort of make up what I think is the foundation of Steampunk.

I like that anachronisms are allowed in the fictional writings as well, it just is a world that imagination can run so wonderfully wild in. And I respectfully disagree with the first bit you wrote here “So it is not so much a basis on Victorian London , but very much the imaginative use of technologies…” , as the clothing of the era is such a huge and IMHO, important part of Steampunk. SP has grown out of books to include outfits and people decorating their homes with “steampunk items” (I was surprised to see on one of the TV networks that shows people decorating or looking for homes, a woman who wanted a “Steampunk House”. Possibly not a great idea, if it is a trendy thing, but whatever made her happy is good I suppose!).

Anyone else want to address the notion that steampunk has nothing to do with Victorian England? I don’t feel like I did very well defending my thesis, so to speak.

Too many of these people are too young to know where steampunk really started.

Do some research and check out Frank L. Baum’s Tik Tok.

That’s where is all started.

I think, from all of these comments, that it is hard to give a definitive time or work that “really started steampunk”. They have done research, they have read books and what I see coming from that are many opinions. Unfortunately, everyone seems so darn sure that they & only they are correct. There is no explanation in your comment as to why you chose that book, so why is your chosen book the first?

Too much of what current day Steampunk is just isn’t included in Baum’s book(s), but I think I know where you are coming from and would add it to a list of books that influenced steampunk. (And if “too many of these people are too young” to have read L Frank Baum’s books, how do you explain that they have read books that are so much older?)

L Frank Baum, and of course this can be argued as well, is known to so many of us who were alive in the previous century because he wrote “The Wizard of Oz” and many other books that take place in Oz, tales of characters made famous in the 1939 film. He is not a niche author unknown to the world 🙂 And darn it, his name is Lyman Frank Baum. He wrote as L FRANK BAUM. Not Frank L Baum. If you are going to be the older and wiser guy, please at least get an author’s name right. I am 46 and the thing that bothers me more than “Millennials” is people who assume that all Millennials are idiots. I am not smarter or more knowledgeable about things just because I was born the year man landed on the moon.

Goggles are only mentioned once in theIndifference Engine and not at all in the other novels.

Surely you meant “The Difference Engine“? The Indifference Engine is an album by steampunk rapper Professor Elemental.

I wonder how collections like the “Gears Of Brass” from Curiosity Quills will (or if they will) influence the direction of Steampunk. They allow for a lot of variation in styles and Steampunk locations in one book.

http://www.amazon.com/Gears-Brass-A-Steampunk-Anthology/dp/1620078031/ref=tmm_pap_title_0

I think Final Fantasy 1 the video game should get a huge honorable mention as an inspiration to the genre. It was probably where I was first introduced to steampunk and many others and was created in 1987.

Featuring an airship, robots, etc mixed with fantasy elements. Final fantasy is definitely groundbreaking.

My first thought was to dismiss a video game. That was thoughtless of me, and I appreciate that you explained why that game relates to steampunk. I graduated from high school that year, so it is pretty wild (in a good way!) to me that those things were out there, and are part of steampunk.

Thank you for having an idea and defending it, I know that I appreciate it.